January has seen a welcome return to the Thames Foreshore after the over-indulgence of Christmas and the New Year. I like this time of year, after all, my ancestors came from both East and North East Europe so cold winters are in my DNA but, much as I love scarves, hats, fleecy gilets and warm woolly jumpers, I find myself starting to long for the return of longer, warmer, brighter days and increasingly shorter nights. Roll on Spring!

My first jaunt to the river in 2024 took place in South West London, my home patch of the capital. Winter aside, the last few months have seen truly miserable weather where it seemed as if it was never going to stop raining. Literally, weeks and weeks of heavy downpours have predictably resulted in very high water levels on the Thames, disappointing low tides and plenty of flooding of the Thames Path, particularly affecting the area covering Putney to Teddington Lock.

During this heavy rainy period, I took my mudlarking friend Tom down to the foreshore in South West London as he’d never been to the river in this neck of the woods and was keen to explore. Without giving away too many secrets (some of the regulars who come here won’t forgive me if I do), the foreshore in this location has a very different look and feel from the foreshore you’ll find in the Centre of London. It’s much more built up with tons of hard core covering potentially interesting find spots, and a longer foreshore where you can walk for some considerable distance wasting a lot of valuable searching time if you’re a newbie. It helps if you’re with someone who can point out where the artefact scatters are.

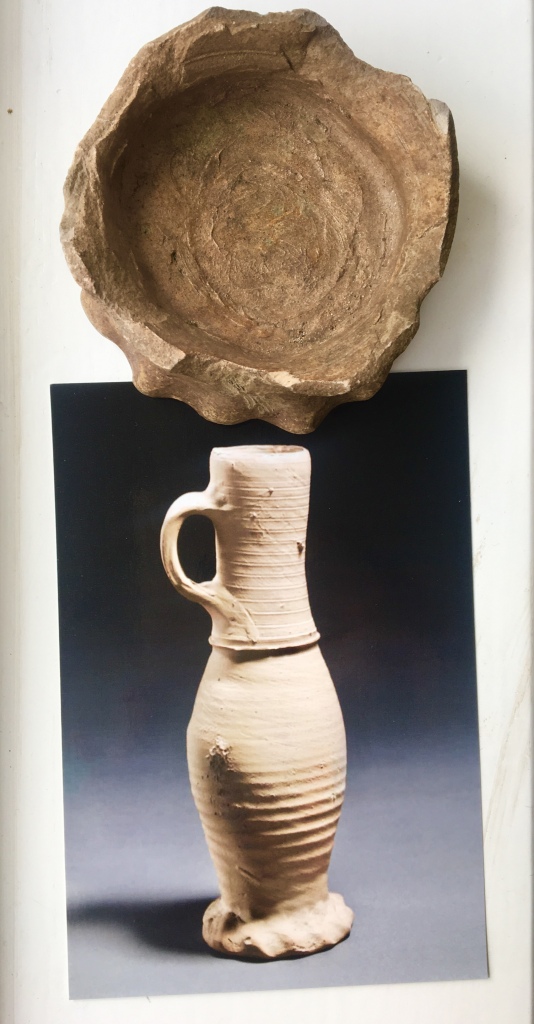

But there are intriguing finds to be made here and many interesting Thames archaeological features. You’ll find pre-historic peat, Iron Age posts, the remains of Anglo-Saxon fish traps, ancient causeways, rotting timbers, Georgian-era mooring posts, old wharves and broken sherds from the potteries that once churned out their wares up on the embankment. The South West London foreshore is home to many thousands of years of the capital’s history, still visible at low tide.

Tom and I arrived on the foreshore with an hour and a half to go before the turn of the tide and made our way slowly downstream, with me pointing out favourite spots and ancient features. I’d already noticed that the tide was far higher than I’d been expecting (moral of this story – check live tide timetables when the weather is dodgy, not just predicted ones) and there was a much stronger prevailing wind at river level than we experienced higher up on the embankment.

We pottered downstream towards an interesting part of the foreshore known for being a location for pottery sherd deposits; clay, stoneware and porcelain fragments tumbling about in the river for centuries before being dumped at low tide for us to search. So engrossed were we in potential finds – Tom found some intriguing metal, I was distracted by an old button – that I took my eye off the river.

I’ve never done this before and Lord knows why I did this time. Mudlarking is engrossing, addictive and it’s easy to lose all sense of time and place. When you’ve spotted something interesting, the temptation to search a bit further, for a bit longer, is extremely strong. ‘We’ve still got plenty of time’ you tell yourself. If only. You’ve probably guessed what happened next… (cue Hammer Horror music.) I looked up from our spot on the foreshore where we were both crouched, chatting away, when I realised to my horror that the tide was coming in fast. It would soon be lapping round our feet, and not that gently either. The wind had picked up and was making itself felt.

As luck, or bad luck would have it, we were midway between two exit points - one further downstream near a well known sports club, next to which is a handy slipway, and one upstream which, although a wee bit nearer, suddenly seemed five miles away. The closest exit was actually a ladder attached to the embankment wall close by but it was rusting, with missing rungs, and decidedly dodgy. No thanks.

There’s something about being in a dangerous situation that seems to numb the brain and make time stand still. I felt guilty that I’d let Tom down by being the (ho ho ho) expert on this part of the river and yet, when it was most crucial, I’d taken my eye off the ball and put us both at risk.

It can be hard to keep calm when the river’s coming in quickly towards you, swirling around you, underneath you, trapping you in its watery embrace. Stupidly I hadn’t brought my usual wellies with me that day but was wearing ordinary walking boots. Fine if you’re hill walking, but of no use when the water’s coming up to your knees fast and the lower half of you is becoming waterlogged.

After nine years of mudlarking I’d forgotten a few cardinal rules – never ignore the pinch points on the foreshore and, on days when the low tide is much higher than expected, the tide will rush in more quickly than you think.

I won’t lie, I panicked.

We made our way as quickly as we could to the main river steps upstream before encountering a savage pinch point which we had no choice but to wade through, the water up to our knee caps now and rising fast. ‘How deep can it be?’ I tried to reason with myself. Well, quite deep and getting deeper. Oh and why am I feeling strong currents gripping my feet? Where have they come from? Who knows. Just keep moving and remember to stay calm and breathe. In for four, out for four. Repeat.

And the mud, oh the mud. Thames mud is gloriously protective when it comes to ancient artefacts, its anaerobic quailities stabilising finds and making them look as fresh as the day they were lost, but if you find yourself stuck in it trying to escape a rising tide it quickly becomes your enemy. Feet sinking fast into it, the mud is like stepping into glue. It impedes your exit and sucks you into its gloopy embrace. At one stage, one of my boots stuck fast and I thought I’d end up bootless. As if that was the only thing to worry about.

Tom stayed calm (more than could be said for yours truly) and somehow we eventually slopped and sloshed our way onto a drier area of foreshore before, thank goodness, the river steps came into sight. We were now home and free, though it took a while for the shakes to leave me. I was mightily relieved I hadn’t been on my own and, when we debriefed afterwards, realised that both the RNLI and Port of London Authority had rescue boats berthed not too far away. We were probably very close to making that call-out but thankfully we didn’t have to. In the words of W. Shakespeare, ‘all’s well that ends well.’

Lesson learnt.

A few weeks after this drama, I made myself return to the scene of the ‘disaster-that-nearly-was’ because I genuinely feared I might have lost my nerve. But the day was clear, river levels were normal and there were quite a few other mudlarks pottering about. I felt safe. Keeping careful watch on the time and the tide this time, I didn’t find very much, but didn’t care. I kept my nerve and gradually began to relax again.

I also made a return visit to the Chelsea Foreshore in January, a favourite spot of mine not often visited by mudlarks. The foreshore here is becoming increasingly narrow and less accessible due to rising sea levels, a side effect of climate change. An extremely good low tide had been predicted that day, the weather was glorious (see the Mediterranean blue skies in the photo above) and it was time to catch up with some of the Chelsea Houseboat community I’ve got to know over the years.

The Chelsea Foreshore, north side of Battersea Bridge, is glorious for so many reasons. Once the location of a Saxon Manor House, also later the home of Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII’s Lord High Chancellor and friend, until the King ordered his execution because Thomas refused to acknowledge him as Head of the Church in England. With friends like Henry VIII, who needs enemies? Thomas More’s eldest daughter Margaret (More) Roper embarked on a dangerous journey by boat from Chelsea to London Bridge in order to retrieve her father’s head, impaled on a spike after his execution, thus saving it from a watery grave. One of the most learned women in 16th century England, I’m a huge admirer of her intelligence and bravery.

And not forgetting that in the 19th century Chelsea was where William de Morgan had a ceramics factory, the perfect forerunner of the area’s later creative, arty, Bohemian reputation before the cost of real estate drove most artists elsewhere.

But I digress. I’d specifically come down to Chelsea to check on the Chelsea fish trap here. Carbon dated to AD 730-900, this is a beautiful thing and one of the few remaining Saxon fish traps on the Thames. Most people passing by on the embankment above barely give it a second glance. I was therefore gutted to arrive and find that even as the waters receded a bit you still couldn’t see a thing, so high was the water level. Chatting to one of the houseboat owners later, I was told the tide levels have been overwhelming in recent months and therefore the fish trap hasn’t actually been seen for quite some time. Eventually it will be claimed by the river, but I hope that doesn’t happen for many years yet.

Below is one of my photos of the V-shaped fish trap taken in 2018. I hope it becomes visible again soon.

But it hasn’t all been doom and gloom and impossibly high low tides. My first visit to the City of London foreshore this year was an excellent one where I made a dream find, something on my bucket list for a very long time.

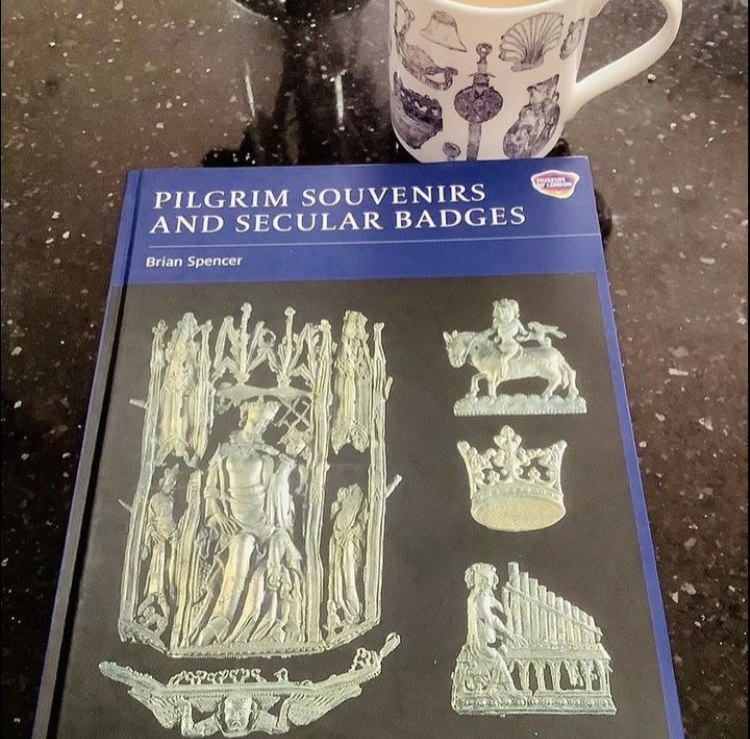

Many mudlarks dream of finding a paw print of some description, usually embedded in an ancient floor or roof tile. Usually these tend to feature a dog or a cat and it was thrilling when one of these was thrown at my feet by wash from a passing Thames Clipper. The tiniest hint of a claw visible in my paw print find indicates a dog was responsible (NB: cats retract their claws when they walk whereas dogs don’t), and a fellow mudlark recently found a tile with a goat’s hoof print. Equally there have been some very big cat paw prints found on mudlarked tiles. I’ve had conversations with larkers about the possible provenance of these and we speculated that they might even belong to a puma or lynx.

This isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds if you consider that the biggest amphitheatre in Roman London was located at the site of the current Guildhall Art Gallery (Guildhall Yard, Aldermanbury, in the City of London). This was once the site of plays, executions, gladiatorial and animal combat and other gory spectacles. There would have been many animal escapes into the city so it’s therefore quite possible that a wretched Roman roof tile maker, having layed out his tiles to dry in the open air, returned to find a massive wild cat paw print embedded deep into his work.

Last, but not least, I’m excited to let everyone know that the first of this year’s mudlarking exhibitions will soon be taking place at the stunning Watermen’s Hall, the historic home of the Thames Watermen and Lightermen, on Saturday 24th February and Sunday 25th February, from 10am -4pm. The venue is located at 16-18 St Mary-At-Hill, near the Tower of London, and entry is free.

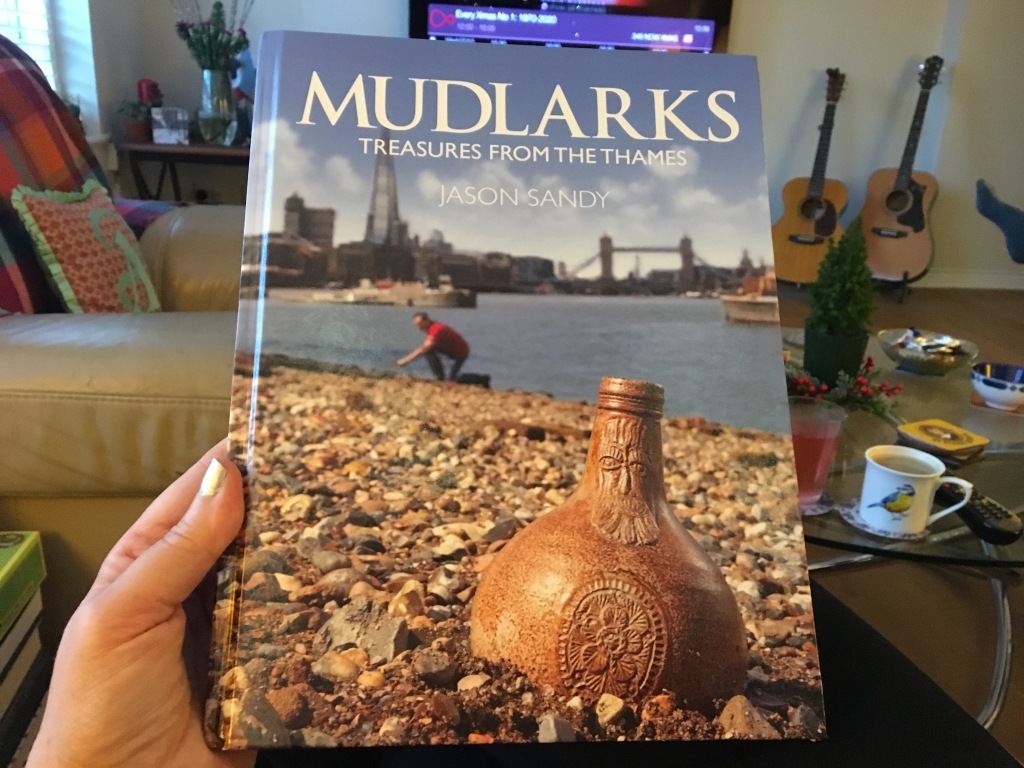

On each of the two days, fifteen mudlarks will be displaying their personal collections and I’ll be exhibiting some of my favourite mudlarking finds on the Saturday, so do please come. For further information on this and other mudlarking exhibitions to be announced later in the year, follow @handsonhistorymudlarks plus event organisers @jasonmudlark aka Jason Sandy, @mudika.thames aka Monika Buttling-Smith and @oldfatherthames aka Marie-Louise Plum, on Instagram.